This is the second Engage and Enable blog post by CNT student member Gabrielle Strandquist in an ongoing series that explains how research works and gives insight into the process for aspiring engineers and scientists. Part one of the series is available here: “What is research, and how do I get involved?“

Part 2: Navigating the research environment

Hello again! Last time, we talked about what research is, how it enables scientific discoveries, why you might want to explore it yourself, and finally, how exactly to get started. This time, I want to talk about navigating some common dynamics you will likely experience, both in the research environment and with the people you will connect with. Learning to navigate these dynamics can help you feel more supported, less stressed, and help you to enjoy your research experience overall. I will note that my experience in scientific research is largely in the STEM fields — science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Research is also conducted in many other fields, such as art history, linguistics and education. Some things I share will generalize to all fields but some things will likely look different depending on the area you are interested in.

Helping people help you

Let’s start with your research adviser. As we mentioned briefly in the last post, this is the person who enables you to learn about the research process in action and will give you the resources you need to actually carry research out. For the purposes of this post, we’ll assume that you have made contact with a professor or researcher who’s work interests you, and they have agreed to advise you in gaining research experience.

Upon acquiring your new adviser, you will meet and have multiple discussions to help you get started. As you progress through the research process, you will continue to meet together to share your progress and to get continual advice. While I cannot predict how your individual interactions with your adviser will go, there is a general concept I’ve discovered that can make this dynamic work well, which is to help people help you. Perhaps counterintuitively, the person seeking assistance can do some things to get the greatest amount of benefit from those they seek help from.

Ask specific questions: How you ask questions can make a big difference in how helpful your adviser can be. Let’s use a simple example of your first meeting with your new adviser. Imagine you are fascinated by the way animals can fly, and you found a professor who studies insect behaviors who has agreed to advise you. You show up, knock on their door, and tell them “I find animal flight interesting. How do I start researching this?” This is a natural question, but it’s vague enough that it contains many possible answers, some of which will be more or less helpful to you. Try to break your question down into smaller, more specific pieces. This will help your adviser give you practical advice that is tailored specifically for your needs. Start by telling them specific things you are curious about, and explain what things you are unsure about. You can reframe your question to something like “I am interested in how different types of wings can determine how long insects are able to stay in the air. Can you explain what are the first steps I should take to start researching this topic?” This gives your adviser some useful information about you. It tells them more specifically what area(s) you’re interested in, and that you need guidance on how to start designing a research study. Then, the advice they give you in response is much more likely to be useful to you.

Know what you don’t know: Let’s say you want to try out research, and you found an adviser to work with who does interesting work, but you haven’t thought about insect wings, and so you don’t have a specific question for your adviser yet. That’s okay too. Instead of asking a specific question, you could say something such as “I am really excited to try scientific research. I think your general area is interesting, but I don’t yet have a specific question I am ready to start investigating. What advice do you have for how to select a specific idea to research? What kinds of projects are you already working on that I might be able to get involved with? Are there papers or books you would recommend I read?” This again gives your adviser good information. They can tell you are new to the research process, that you are open to hearing about different project ideas, and that you don’t yet know what exactly you want to research. They will now be better able to advise you in next steps you can take.

Bring an agenda: You will eventually get started on some project or task and will continue to meet with your adviser along the way. When I meet with advisers or people I do group projects with, I find it helpful to start the meeting with an agenda, or a list of things I want to discuss or ask about. This act of writing things down is helpful in figuring out where you need the most help, and it helps to navigate your discussion in a direction that will be useful to you. Of course, the discussion might deviate from your original agenda, but it’s helpful to have a starting place, as well as a record of questions you still have that you perhaps didn’t have time to cover in a meeting.

Communication: We all know communication is key in all aspects of life. When you get started working with a new adviser, I find it helpful to ask them what their preferred type of communication is. Do they prefer email or other forms of communicating? How often would they like updates on your progress? What is a good way for both of you to keep track of the work you are doing? Asking basic questions like this at the beginning of your relationship can help you both stay on the same page.

Research as a community

As you are likely inferring, having someone to guide you through the research process, including finding answers to big-picture questions and understanding smaller specific procedures, is going to be vital to help you have a successful research experience. Having said this, it’s good to be aware that the person guiding you, sometimes called your “research mentor”, may not always be the research adviser that you initially reached out to. You may receive guidance from other students or researchers who also do research for your same adviser. This is a very beneficial thing, partly because you will have access to more help than what your adviser alone can give you, and partly because learning from more than any single person is a great way to learn and expand your mind. Together, your adviser and any other people who work for them form a group that is often called a “research lab.”

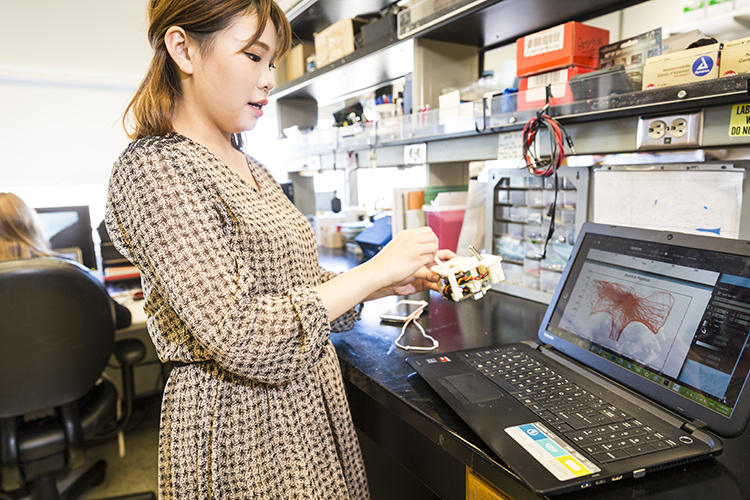

Research labs: The phrase “research lab” might sound strange, depending on your preexisting experience and knowledge. When I first heard this term, I envisioned people in white lab coats and goggles pouring brightly coloured liquids into beakers. Looking back, I think I was imagining some kind of chemistry workspace. More generally, a research lab refers to a group of people who are connected to each other by the intersection of their research interests. While a lab can consist of people in white lab coats, it can also be people in an office on their computers, or people out in nature conducting experiments in the field. A lab is defined by the people in it, and these are the people who engage in scientific research.

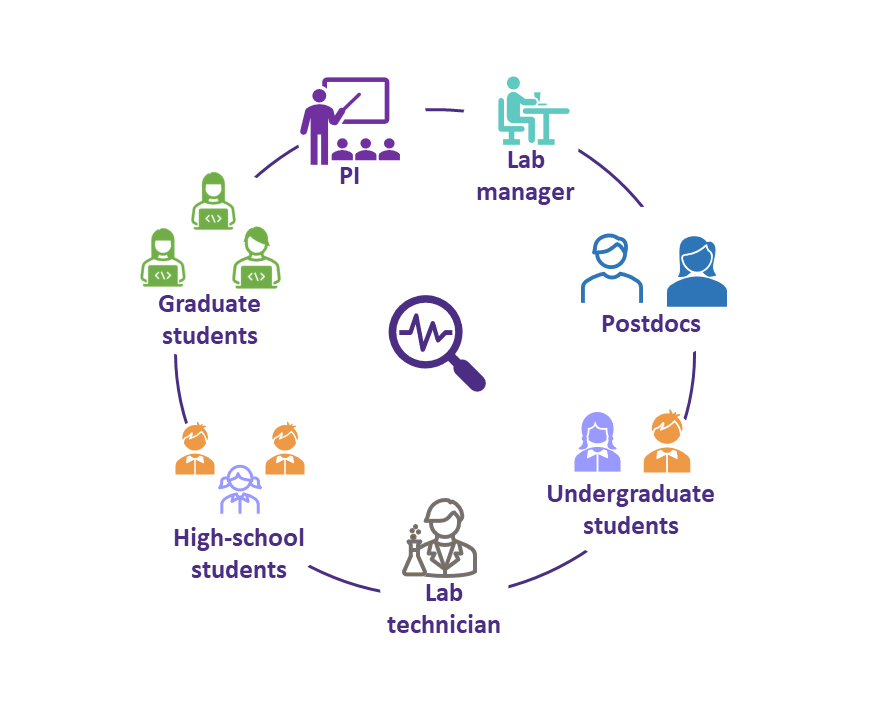

The many roles of a lab: In any given lab people fill various roles. Understanding these roles can really help you find people to talk to, to seek advice from, and generally to understand your surroundings. First, there is your research adviser who is sometimes referred to as a “Principal Investigator” (or PI for short), who oversees everyone’s duties in the lab. This means it’s the PI’s responsibility to ensure there is sufficient funding to pay for the work being done, that the research being carried out is done ethically and responsibly, and that the overall output of the group is going in useful directions. The rest of the people in the lab work for and/or are advised by the PI to one extent or another. For larger labs, there might be a lab manager who helps coordinate lab needs and activities. Sometimes there are postdoctoral fellows (postdocs for short), who conduct research after having attained their Ph.D and are well-versed in the research process. Graduate students are those seeking a Ph.D. or master’s degree and are relatively early on in their research careers. There are sometimes undergraduate and high-school students who gain research experience while simultaneously working on their degree or diploma. Depending on the lab, there could be lab technicians, software engineers, or other people who help carry out various work for the lab but are not necessarily working toward a degree. Of course, the sizes of labs vary widely; sometimes there are no postdocs, or no undergraduate students, etc.

A lab as a community: All of these people, regardless of their title, background and levels of experience, usually work in areas that are at least somewhat related to each other. This means that when you join a research lab, you are joining a community of people to work alongside, which is one of my favorite aspects of scientific research. Each person in the lab will contribute to specific projects, but these projects may share common themes driven by the PI. As with any community, every lab will have its own interpersonal dynamics, work policies and culture. Just like finding the right person to be your adviser will greatly improve the success and enjoyment of carrying out research, finding a research lab with a culture you are comfortable in will improve your experience as well. Often there are group projects, or “collaborations”, between members of the same lab, and it’s common for people with varying levels of experience to mentor and assist those who are less experienced. In fact, just like I previously described how to choose potential advisers by looking at the work they do, you can also look up the work conducted by postdocs and graduate students within the lab of the PI who first caught your interest. This can be accomplished by finding the people who work for the PI (generally listed on the PI’s personal or university web page) and by reading about what projects, posters or papers they have written. This will give you an even better feel for what kind of research the lab likes to explore and may give you more ideas for things you might be interested in trying out yourself.

The final say: who decides what to research?

As we mentioned earlier, the PI is responsible for the research conducted in their lab. One thing this implies is that the PI decides what kinds of research the lab will pursue. You don’t usually find labs that simultaneously study history, sculpture, and engineering (although we could make a case for why labs should combine research from more disparate areas, a possible topic for another day!). Generally, there is a theme that the work in a lab corresponds to. Although this theme is initially determined by the PI, research often branches into new directions that the PI may not have initially planned or anticipated as more students join the lab.

A two-way street: To carry on with our first example, let’s say the PI of the lab you just joined studies insect behavior, but you noticed that they don’t investigate flight or wing dynamics. If you are interested in studying insect flight, your joining the lab could generate a new branch of research conducted in the lab. This is all to say that while your choice of PI and lab that you join will inform the overall area(s) you explore, there is usually some freedom to devise specific projects that you might want to carry out. In other words, don’t feel that the research areas you explore must be constrained by what your PI has done in the past. There is room to explore new ideas and your PI will likely encourage you to do so! In fact, students coming to a lab with their interests and ideas is an essential part of how labs grow and flourish. A PI offers guidance and support and in turn students bring fresh ideas and talents. This “two-way street” dynamic helps creativity and intellectual freedom to develop, and is beneficial to everyone involved.

There are many aspects to research, both in its process and the people who are involved. As time progresses, you will learn an immense amount about how research is conducted by observing your fellow researchers and by asking them questions. Getting a “lay of the land” can help you adapt more quickly, and I hope some of these thoughts have given you a head start in doing so. Next time, we will look at some useful things you can start doing that will give you a “super-boost” in being effective and successful in the work that you choose. They are things I wish I had started sooner myself, so I am eager to share them with you in my next post.